[ad_1]

Jelle Barkema

How concerned should policymakers be as UK business insolvencies have soared to 60-year highs? This phenomenon has been extensively covered in the media; with media outlets attributing the record-breaking numbers to a ‘perfect storm’ of energy prices, supply-chain disruptions and the cost of living squeeze. Insolvencies are a popular measure of economic distress because they have implications for both the financial system and the real economy. For the financial system, an insolvency generally means creditors will incur losses. Insolvent firms will have to cease trading and lay off workers, which affects the real economy. In this blog post, I assess the evolution of corporate insolvencies over time, including the post-Covid surge to understand what these record numbers mean for the UK economy.

What is an insolvency?

Let us start with the basics – what is an insolvency? An insolvency occurs when a company can no longer meet its debt obligations. These obligations can be bank loans, but can also include outstanding electricity bills or tax liabilities. A director of a company is obliged to file for insolvency once they realise that their company cannot pay its debts. Hence, most insolvencies are voluntary and instigated by the company itself. These insolvencies are called creditors’ voluntary liquidations (CVLs). In most other cases, the company in question has failed to abide by this obligation and creditors are compelled to go to court and issue a so-called winding-up petition. A judge will then consider the petition, and, if deemed valid, will issue a winding-up order. Following either CVL or a winding-up order, a liquidator will take control of the company and attempt to liquidate its assets – the proceeds of which will be used to repay (some of) the debts. In the remainder of the blog, I will refer to winding-up orders and CVLs as liquidations. Insolvencies, in contrast, will include all insolvency procedures, even those that do not result in liquidation (like administrations).

Insolvencies over time

In the UK, the liquidation rate, which measures the number of liquidations per 10,000 firms, is cyclical and has followed a clear downward trend. Chart 1a below shows increases in the liquidation rate (orange line) after the early 1990s and 2008 recessions. Overlaying this trend with a line depicting Bank Rate (blue line) shows that the long-term decline in the liquidation rate coincides with a loosening in financing conditions. This is consistent with the likelihood of a firm going insolvent being a function both of the economic environment and the cost of their debt. The literature corroborates this: Liu (2006) finds that interest rates are strong predictors of the liquidation rate in the UK, both in the short and long term. In contrast, a measure of corporate dissolutions since the mid-1980s (Chart 1b, green line), which tracks all company exits (whether they had debt or not), seems more stationary and follows real economy developments – as measured by real GDP growth – more closely. It is important to add that structural changes to the insolvency regime and/or company register also play an important role in determining insolvency and dissolution trends. For example, Liu finds that the 1986 Insolvency Act, which introduced the administration process as an alternative to liquidation, caused a structural downward shift in UK liquidations.

Chart 1a: Corporate liquidation rate and Bank Rate over time

Chart 1b: Inverse real GDP growth and corporate dissolution rate

Sources: Bank of England, Companies House and Insolvency Service.

Note: Liquidation rate equals the number of liquidations per 10,000 firms. Dissolution rate equals the total number of dissolutions divided by the total number of incorporations.

Setting the record straight

So given that Bank Rate was at an all-time low until 2021, how did insolvencies reach an all-time high? Some necessary nuance to this record is that it only pertains to voluntary insolvencies and, importantly, does not account for the growth of the company register over time. The liquidation rate mentioned in the previous paragraph does factor this in and shows the 2021 numbers are nowhere near their all-time maximum. Moreover, insolvencies are only a fraction of all firm exits (4% in 2022) so by themselves are not a reliable gauge of real economy risk.

That is not to say that all is well. UK corporates are facing a unique series of shocks with Covid followed by a sharp increase in energy prices. In addition, financial conditions are tightening faster than they have in decades, making refinancing more challenging and thus insolvency more likely. Business insolvencies can trigger defaults and significant write-offs, which, in theory, could threaten financial stability if occurring in large numbers or in particular sectors of the economy.

Analysing insolvencies at a company-level

To better understand the steep increase in insolvencies and potential financial stability risk, it is helpful to move away from aggregate numbers and to look at insolvencies at a micro-level. I do this by web scraping individual insolvency notices from the Gazette and matching them to company balance sheets obtained through Bureau van Dijk. Having this matched, firm-level data allows us to analyse patterns across insolvency types, sectors, age and size bands.

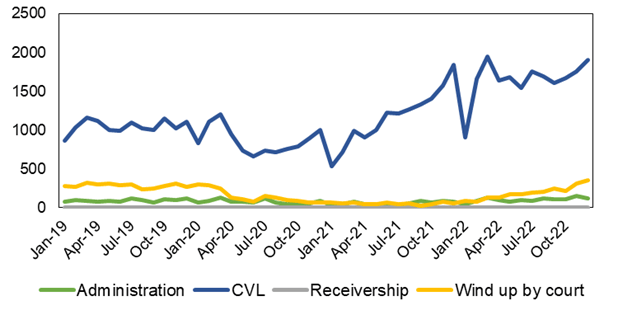

A first look at the data reveals insolvencies are partially making up for lost ground during the pandemic. Targeted legislation meant that Covid-related insolvencies were temporarily suspended. The suspension of lawful trading rules (targeting CVLs) was in effect from March 2020 until June 2021 while restrictions on winding-up petitions (targeting compulsory insolvencies) remained in place until March 2022. After these measures had been lifted, insolvencies increased rapidly. Chart 2a below demonstrates this clearly: monthly voluntary insolvencies (blue line) fell significantly in 2020, but have since moved past their pre-Covid average, reaching all-time highs. Meanwhile compulsory liquidations (yellow line) were slower to recover but are now surpassing 2019 levels. As of 2022 Q4, the difference between cumulative insolvencies in the 11 quarters before Covid and the 11 quarters since Covid (the ‘insolvency gap’) has almost disappeared.

Chart 2a: Business insolvencies by category (number of insolvencies)

Chart 2b: Business insolvencies by company size (number of insolvencies)

Sources: Insolvency Service, Gazette and Bureau van Dijk.

Note: Micro firms have <£316,000 in total assets, small firms between £316,000 and £5 million, medium firms between £5 million and £18 million, and large firms over £18 million.

Micro firms drive the recent surge in insolvencies

Analysing the post-Covid insolvency surge across company size bands shows that it is largely driven by micro firms – those with less than £316,000 in assets (Chart 2b). In 2022, 81% of insolvencies comprised micro firms, compared to 73% in 2019. This uptick can in part be attributed to timing. The insolvency process tends to be more drawn out for large firms, so it will take longer for the impact of Covid and the energy price rises to be reflected in the statistics. But that is only part of the story. Data from responses to the ONS Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS) shows that smaller firms (fewer than 50 employees) consider themselves at a substantially higher risk of insolvency compared to their larger peers (Chart 3a). At the latest wave (ending December 2022), small firms perceived the risk of insolvency to be twice as high. This corresponds with the disproportionate impact of rising energy prices on small businesses (Chart 3b).

Chart 3a: BICS – Business at moderate/severe risk of insolvency (share; by number of employees)

Chart 3b: BICS – Energy prices as main concern (share; by number of employees)

Source: ONS BICS.

Note: Different BICS waves will not necessarily contain the same questions, hence the difference in x-axes between the two charts.

The prevalence of small firms in the insolvency numbers is reassuring from a financial stability perspective; the UK banking sector is well capitalised and exposure to these companies is simply not large enough to present a material risk. Moreover, because of the unprecedented financial support provided during the pandemic in the form of loan schemes, some of this debt will be guaranteed by the government. Indeed, close to 60% of all insolvencies between May 2020 and March 2022 were incurred by firms who had also taken out a Bounce Back Loan. This is also reflected in the company-level data with small firms boasting higher debt levels prior to insolvency compared to pre-Covid (Chart 4). The debt to assets ratio of young firms going insolvent is two times higher in 2022 than it was in 2019.

Chart 4: Indebtedness prior to insolvency by size (total debt/total assets)

Sources: Gazette and Bureau van Dijk.

Sectoral and age distributions remained unchanged

Financial risk could also arise if insolvencies are concentrated in particular parts of the economy. There is no evidence of this so far: the sectoral distribution of insolvencies, for example, looks very similar to 2019 despite the heterogenous impact of the pandemic. One explanation for this is that industries particularly hard hit by the pandemic, like accomodation and food, are also significant beneficiaries of government support schemes. The same goes for the age profile for insolvent firms, which has largely remained the same compared to before the pandemic despite widespread dissolutions among newly incorporated firms.

A succession of macroeconomic shocks has pushed UK business insolvencies to all-time highs. Insolvencies only constitute a small share of all firm dissolutions so it is not an accurate representation of real economy risk. Furthermore, the majority of firms going insolvent are small while exposures are in part government-guaranteed, so I cannot conclude they constitute an imminent financial stability issue either. However, this can change as macroeconomic challenges continue to accumulate, government loan payments become due, financial conditions tighten, and larger, more complex insolvencies start to crystallise. This is definitely a space worth watching.

Jelle Barkema works in the Bank’s Financial Stability Strategy and Risk Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Image source: Shutterstock.

[ad_2]