[ad_1]

Bloomberg) — The worst was meant to be over for San Francisco. Coders were returning from Lake Tahoe and Miami, ChatGPT was all the rage and a downtown emptied out by the pandemic was showing signs of life.

Then came an old-school bank run.

In a matter of weeks, a city better known as a tech hub has become a center of the financial turmoil that’s sent shockwaves around the world. Silicon Valley Bank’s sudden failure shattered the preeminent lender to the venture-capital firms and startups that help fuel the region’s economy. First Republic Bank, a San Francisco institution for almost four decades, has seen its stock plunge as investors worry it’s next.

Now San Francisco, where the next new thing was always around the corner, is struggling to figure out its future. With the spigot of easy money that propelled its tech and finance industries turned off, the city is facing a constellation of economic challenges unlike any in its boom-and-bust history.

The tech explosion that fueled unprecedented wealth in the last decade gave way to a pandemic exodus of companies and talent from the Bay Area. The money-flowing days of 2021 were followed by soaring interest rates and a stock market rout in 2022. This year, the banking crisis and mass layoffs from the likes of Twitter Inc., Salesforce Inc. and Meta Platforms Inc. threaten to derail a nascent recovery.

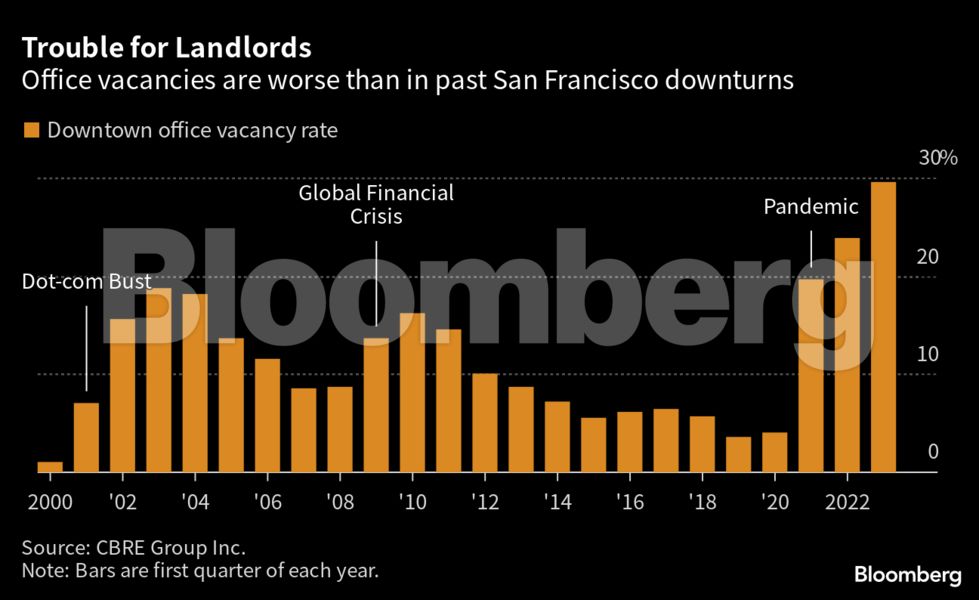

Pain is already apparent: On Friday, city officials forecast a $780 million deficit for the next two fiscal years, more than $50 million worse than projected in January. Downtown San Francisco’s office-vacancy rate soared to a record 29.5% in the first quarter, up from just 4% before the pandemic, with landlords expected to come under even greater strain as loans come due. Startup founders are wondering how their funding rounds will come together.

It’s a “triple whammy,” said Michael Covarrubias, chief executive officer of local real estate developer TMG Partners and former head of the Bay Area Council, a group of business leaders focused on the region’s economic vitality. “We’ve never had this much vacancy in downtown San Francisco and a pandemic, followed by the work-from-home thing, followed by the banking thing started by Silicon Valley Bank and now sort of matriculating into the big banks, commercial loans and all that.”

Downtown Malaise

The effects can be seen in places like San Francisco’s Mid-Market area, once viewed as a symbol of a newfound tech era after city officials used tax incentives to lure Twitter Inc. to set up its headquarters at 1355 Market St. in 2011.

Now, Elon Musk’s Twitter is being sued for not paying rent on the building, and the coffee shop inside is closed. Nearby tenants including Uber Technologies Inc., Block Inc. and Reddit Inc. have given up or cut down on space. A Chase bank on the corner is fully shuttered, and a Wells Fargo ATM across the street was entirely removed and boarded up. The neighborhood’s location near the Tenderloin district, known for open-air drug use and crime, adds to a sense of grittiness.

“We used to have a morning rush, a lunch rush and a closing rush,” said Heidi Colin, a cashier at Dough and Little Griddle, a breakfast and pizza spot on the first floor of what used to be Uber and Block’s headquarters. “Now it’s a mini rush, and we’re lucky if we even get it.”

San Francisco’s employers are embracing remote work, with the metro area consistently ranking among the worst in the US for return-to-office measures. Ridership on the Bay Area Rapid Transit service has only returned to about 40% of pre-pandemic levels, leading to a fiscal crisis and the threat of service cuts that would make it even more difficult for commuters to come in.

For Mayor London Breed, restoring San Francisco’s luster will take much more than resuscitating its empty financial district. She’s supporting legislation to relax zoning regulations so that office buildings can be converted to residential use, and is seeking to diversify the tech-centric economy with tax breaks and other incentives to lure different types of industries.

“People are trying to equate success to the number of people who return to the office in downtown San Francisco, and we are not going to be what we were before the pandemic,” she said in an interview. “We’re just going to be something different.”

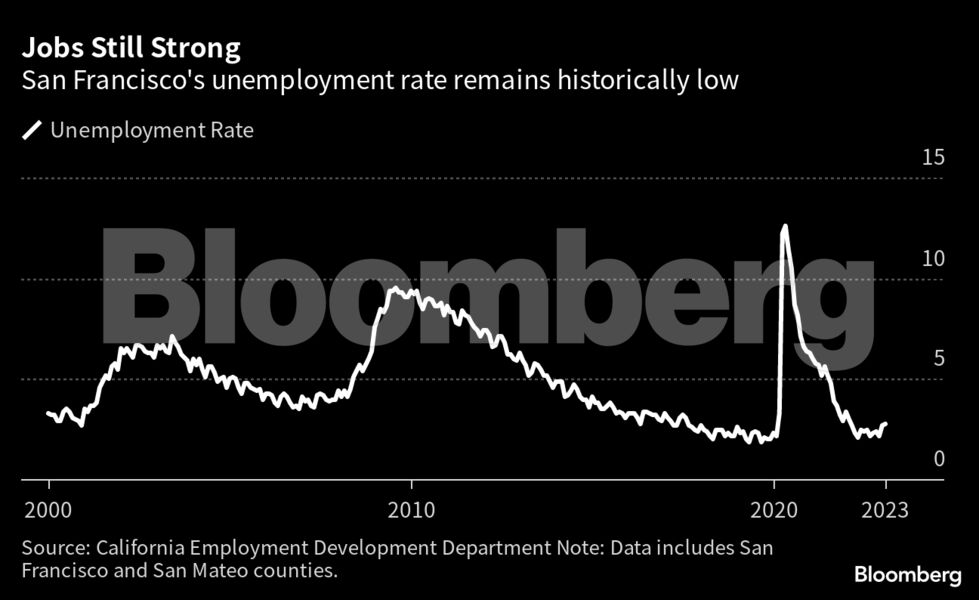

There are many reasons for optimism. The number of visitors to the city grew by 29% to 21.9 million in 2022, according to the San Francisco Travel Association. ChatGPT, from San Francisco-based OpenAI, has sparked hopes that artificial intelligence will be a new driver of the tech economy. And the metro area’s unemployment rate as of February was 2.8%, historically low and less than the US rate of 3.6%.

Still, the rate is up from 2.2% in December. San Francisco County and adjacent San Mateo County, home to Meta, lost a combined 11,000 jobs from December through February. Meta last month announced plans for an additional 10,000 layoffs globally.

“To lose this many jobs in three months is not something we’ve seen in the last few years,” said San Francisco Chief Economist Ted Egan. “It’s definitely a warning sign.”

Wall Street West

The hope is that the SVB crisis won’t make things worse.

Long before the tech industry remade the Bay Area, San Francisco was a banking powerhouse. Nicknamed the Wall Street of the West, the city boomed as a financial hub during California’s Gold Rush, with private banks accepting gold deposits and issuing their own currency before the US established the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Wells Fargo & Co. offered stagecoach transit and banking services; the Bank of Italy established in the city by produce mogul Amadeo Giannini in 1904 eventually became Bank of America.

But the financial sector has shrunk considerably since San Francisco’s banking heyday, said Egan, accounting for about 16% of the city’s gross receipt taxes as of 2019.

Charles Schwab Corp. — a brokerage also under strain — moved its headquarters to Texas at the start of 2021, a relocation cited as an example of the city’s failure to nurture home-grown companies. Wells Fargo remains based San Francisco, but New York has increasingly become the nexus of power for the bank, with CEO Charlie Scharf based there. Edith Robles, a spokeswoman, said the company isn’t moving its headquarters.

“Wells Fargo was founded in San Francisco in 1852 and the city remains important to the bank,” she said.

The March 10 collapse of Santa Clara-based Silicon Valley Bank — a lender to not only the tech community but to industries from solar to wine — reverberated across the region. First Republic Bank, too, has woven itself into the fabric of San Francisco, offering private banking for the wealthy, loans for small businesses and jumbo mortgages to finance the city’s exorbitant housing costs. Bay Area clients accounted for 40% of the bank’s $176 billion in deposits as of the end of last year.

Read more: First Republic’s Rich Clients Reckon With ‘Chorus of Cassandras’

Janice Jensen, CEO of Habitat for Humanity in the East Bay and Silicon Valley, has banked with First Republic for more than 15 years, but she moved money to protect uninsured deposits against losses in case the bank failed. It was a good business decision but a tough emotional choice, she said, because First Republic helped her avoid layoffs during the pandemic by getting her money under the Paycheck Protection Program and helping her set up online housing counseling classes.

“To lose First Republic, that’d be terrible,” said Jensen, whose nonprofit has built hundreds of homes with First Republic financing. “It’s not just a bank. If it went away, it’d be a whole lot of tentacles into the community. That’s further stress on an already stressed area.”

The bank’s share declines have stabilized after SVB was taken over by First Citizens BancShares Inc. and officials including JPMorgan Chase & Co. CEO Jamie Dimon and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen moved to shore up its finances. Still, its stock is down almost 90% this year.

Empty Offices

Even if the panic brought on by SVB’s collapse subsides, San Francisco — and banks — still face a lurking crisis from its troubled commercial real estate market.

Dealmaking has plunged, hurting revenue in a city where voters approved a property transfer tax increase in 2016. Closing prices on the few office buildings that traded have fallen by half from pre-pandemic heights, when properties fetched $1,000 a square foot. And as office vacancies climb, it’s unlikely that there will be a wave of new leases in the near-term, said Colin Yasukochi, a researcher at CBRE Group Inc.

“Usually in uncertain times, companies will delay decisions as long as possible,” he said. “Not moving is often cheaper than moving.”

On top of soaring vacancies, rising borrowing costs are undermining property values and making it tough for landlords to refinance debt. Columbia Property Trust, a unit of Pacific Investment Management Co., is more than 60 days delinquent on mortgage payments for two downtown office buildings. Veritas Investments, one of the city’s largest owners of rental housing, defaulted in November on a $344 million mortgage on 62 apartment buildings, which were appraised at more than $1 billion less than three years ago.

Read more: Tech Retrenchment Hammers Landlords With Glut of Empty Offices

Multifamily properties are selling for 15% below pre-pandemic levels, according to Brandon Geraldo of brokerage Jones Lang Lasalle Inc. That’s a stark contrast with most cities, where apartment values and rents soared after the pandemic, he said — a silver lining for tenants in a place that’s long been one of the nation’s costliest markets.

“San Francisco through Covid has become one of the most affordable markets relative to where incomes are,” Geraldo said.

San Francisco does love a gold rush, and the allure of riches (and perhaps slightly more affordable rents) is bringing plenty of people back to the city, along with hopes that it will rebound just as it always has from devastating busts. The Bay Area trails only Austin, Texas, in the share of LinkedIn members who have arrived in the last 12 months, according to the social-networking company.

“There’s been more hackathons in the last five weeks than I’ve seen in the last five years,” said Ann Bordetsky, an investor at VC firm New Enterprise Associates. She’s seen more founders moving back, even if they are keeping their teams remote and distributed.

Still, the renewed interest in San Francisco is more in spite of the city, not aided by it, Bordetsky said. Longstanding problems like safety, homelessness and affordable housing haven’t changed all that much. Tech founders are gravitating to areas like the Embarcadero or Hayes Valley, now nicknamed “Cerebral Valley,” rather than the traditional downtown buildings, she said.

And while the city’s proximity to world-class universities, Silicon Valley and its venture capital remains unchanged, the pandemic more broadly has shifted the landscape of opportunity for tech entrepreneurs. “What people have been doing is they say ‘listen, let’s throw a dart at the map, if it lands in Sun Valley, or Park City, or Scottsdale, or Austin, or Miami, let’s move,’” Jack Selby, managing director of Thiel Capital, said Thursday at a conference in Miami Beach. “Because you can literally move basically anywhere in the United States and the cost of living will be significantly lower than it is in the Bay Area.”

Breed has heard it all before. In her February State of the City address, the mayor pointed to cataclysms from the 1906 earthquake to the bursting of the dot-com bubble that brought in a spate of naysayers, only to have the city rebound stronger than ever.

“You can write us off, but it better be in pencil,” she said. “We have proved you wrong every time before, and soon we will again. It’s what we do.”

To contact the authors of this story:

Biz Carson in San Francisco at [email protected]

Karen Breslau in San Francisco at [email protected]

John Gittelsohn in Los Angeles at [email protected]

© 2023 Bloomberg L.P.

[ad_2]