[ad_1]

Gerardo Martinez

In 1936, John Maynard Keynes coined the famous term ‘Animal Spirits’ to illustrate how people take decisions based on urges, overlooking the benefits and drawbacks of their actions. To what extent are prices of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) assets driven by the sentiment of market participants, as opposed to economic fundamentals? To answer this question, I make use of Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools and an original corpus of tweets to capture market sentiment around climate change. Estimating a factor model, I find that sentiment is associated with immediate returns of climate change related stock indices. These results are stronger for days with the most extreme returns. Market sentiment might be particularly useful in explaining large movements in ESG asset prices.

Up and coming: ESG assets

ESG assets are portfolios of equities and bonds whose underlying companies satisfy environmental, social and governance factors. They represent a fast-growing share of asset management portfolios: according to Bloomberg Intelligence, ESG exchange-traded funds (ETFs) cumulative assets reached over $360 billion in 2021, and that figure is expected to reach $1.3 trillion in 2025.

The growing importance of these assets makes ESG returns and volatility an important object of study. First, we would like to measure to what extent market sentiment around ESG can drive asset prices. And if the effect is significant, ESG assets could act as a trigger or amplifier of stress in financial markets if there was a significant adverse turn in sentiment.

To the best of my knowledge, this post is the first to use a sentiment indicator on climate change, constructed using NLP tools and an original sample of tweets, as an input into models that explain asset returns. I look at three stock market indices designed to measure the performance of companies in global and UK clean energy-related businesses:

- The S&P Global Clean Energy Index (GCEI).

- The FTSE Environmental Opportunities Renewable and Alternative Energy Index (EORE).

- The FTSE Environmental Opportunities UK Index (EOUK).

Chart 1 plots the performance of the indices, which move closely with political events related to climate change policy.

Chart 1: Climate change related stock indices and overall benchmarks (01/01/2016 = 100)

Sources: Bloomberg and author’s calculations.

All about attitude: measuring market sentiment

To construct a measure of market sentiment around climate change, I extract from the Twitter API an original sample of over 700,000 tweets filtered by keywords closely associated with climate change. I restrict my search to English-language tweets posted in the US and UK. I follow a standard pipeline to remove duplicates, clean and pre-process the text of each tweet.

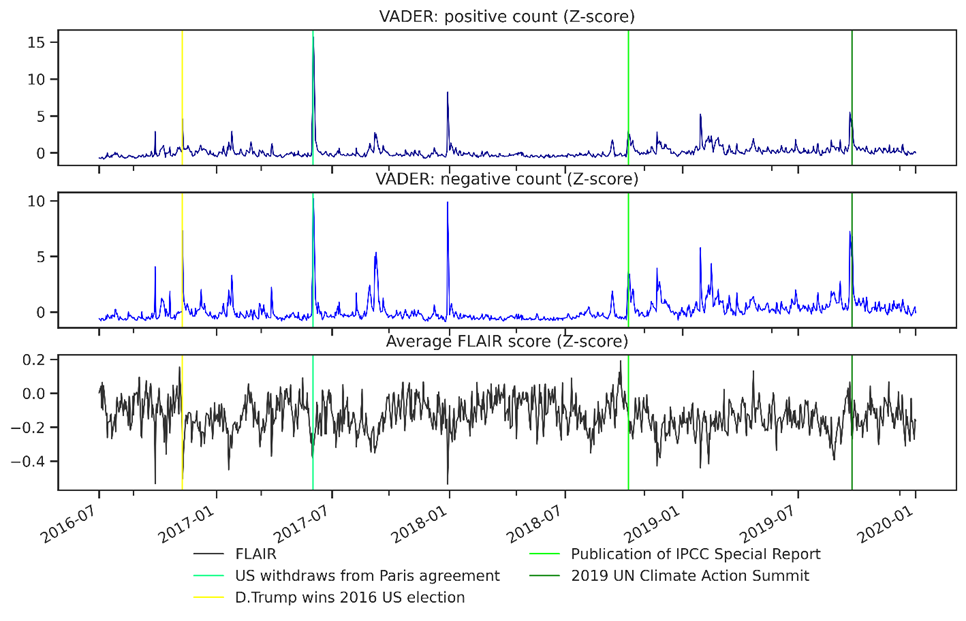

I apply two existing, pre-trained Natural Language Processing tools (FLAIR and VADER) to the resulting data set. Chart 2 shows the resulting counts of tweets, divided into positive and negative sentiment according to VADER. It also shows the average FLAIR score for every day in the sample. The three metrics are normalised using the Z-score.

There is a strong correlation between the three indicators. Spikes in the count of negative and positive tweets track extreme values of the average FLAIR score closely. These extremes are often linked to political developments around climate change.

Chart 2: Measures of market sentiment around climate risk

Source: Author’s calculations.

Linking market sentiment and one-day ahead returns

To assess to what extent market sentiment influences ESG asset returns, I estimate a factor regression which links the return on the ESG indices to the VADER and FLAIR scores, controlling for additional factors. These factors include the price-to-earnings ratio of each index, the difference between 20-year and 30-day government bonds (time-horizon risk), investment-grade corporate bond spreads (confidence risk), and the returns of a benchmark index (the S&P 500 in the case of the S&P GCEI, and the FTSE 100 for the FTSE EORE and FTSE EOUK indices).

Table A shows that the effect of market sentiment on returns is statistically significant, but modest. The effect is especially clear for the FTSE EORE index. A 1 standard deviation increase in the count of positive tweets is associated with an increase in daily EORE returns of 10 basis points. Reversely, a 1 standard deviation increase in the count of negative tweets is associated with a decrease in daily returns of 14 basis points. For comparison, the unconditional standard deviation of EORE returns in the sample is of 76 basis points.

Note that the effect of positive and negative tweet counts is similar, but of opposite signs. This is encouraging, as it is natural to interpret market sentiment as the difference between positive and negative individual sentiment.

The estimated effects on the S&P GCEI are of similar magnitude and direction, although the coefficient on the count of positive tweets is not significant at the 10% significance level. However, I find no significant effect of positive and negative tweet counts on FTSE EOUK returns. One possible explanation is that the FTSE EOUK index captures UK companies. In contrast, the majority of tweets in the sample were located in the US, and thus might not capture sentiment around climate change specific to local UK factors.

Focusing our analysis on the 10% most extreme (highest and lowest) returns yields larger coefficients on the VADER sentiment metrics. For example, on the day of the 2016 US election, I estimate that market sentiment lowered returns for the FTSE EORE and S&P GCEI by around 30 basis points, based on the difference between the negative and positive tweet counts. The regression on the more extreme sample estimates that effect to be of 300 basis points, which would explain 60% and 85% of the observed negative returns respectively.

While FLAIR and VADER scores react to important events, they are likely to contain a significant amount of noise on a day-to-day basis. Adding periods with smaller returns to the sample is likely to add noisy FLAIR and VADER observations, which drives down the regression estimates towards zero.

The opposite happens to FLAIR sentiment scores. Taking the regression results at face value, days with negative market sentiment are associated with higher returns. But on days with extreme returns, the effect of sentiment as measured by FLAIR scores disappears. Given the strong correlation between FLAIR and VADER scores, it is likely that sentiment is captured through the VADER scores, with FLAIR estimates driven mostly by noise.

Table A: Effect of market sentiment on ESG returns

| Coefficients | |||||||||

| (a) 1-day returns | (b) 5-day returns | (c) 1-day returns, 10% most extreme observations | |||||||

| Independent variable | FTSE EOUK | FTSE EORE | S&P GCEI | FTSE EOUK | FTSE EORE | S&P GCEI | FTSE EOUK | FTSE EORE | S&P GCEI |

| VADER positive count | 0.02 | 0.1** | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 | -0.26 | 1.07** | 1.17** |

| VADER negative count | -0.05 | -0.14** | -0.16** | -0.02 | -0.05 | -0.1 | 0.13 | -1.07** | -1.39*** |

| FLAIR average score | -0.33** | -0.15 | -0.16 | -0.09 | 0.13 | -0.07 | -0.65 | 0.55 | -0.28 |

***p < 0.01: coefficient significant at the 1% level **p < 0.05 *** p<0.10

Table A also shows the same set of coefficients, estimated on five-period-ahead returns. No coefficient is statistically significant. This is encouraging: we would expect changes in market sentiment to be quickly included in the information set of investors and for market prices to adjust accordingly.

Market sentiment across time

In order to shed light on the dynamic relationship of ESG returns and market sentiment (as well as the other factors), I run a Vector Autoregression (VAR). I am particularly interested in the pass-through of shocks in the market sentiment indicators to ESG returns. To that effect, Chart 3 plots the variance decomposition of the estimated model for each of the three ESG indices. The variance decomposition is computed over forecast errors over a 20-day horizon, and then averaged for ease of exposition.

The three market sentiment indicators together explain a very small fraction of the forecast error variance. Combined with the results of the regressions for the one-day and five-day returns, these findings suggest that shocks to market sentiment do not explain returns beyond a one-day time horizon. One interpretation is that shocks to market sentiment typically happen around important political events (see Chart 3), and that market participants are able to quickly price in their effects, hence having little effect on returns over a longer horizon.

Chart 3: Variance decomposition, average over 20-day horizon forecast

Source: Author’s calculations.

Conclusions

The results of this analysis suggest that market sentiment on climate change is associated with one-day returns of ESG stock indices. The estimated effect is of modest magnitude, but is especially clear and strong when the analysis is limited to the periods with the most extreme returns. However, it is not universal across all indices and sentiment indicators. And a dynamic analysis shows that exogenous shocks to market sentiment do not explain returns beyond a one-day horizon.

Nevertheless, these results have several implications for financial markets regulators. Firstly, they open the door to enriching models for forecasting asset prices, by including additional inputs such as fundamentals or market sentiment and new tools such as machine learning models. Secondly, regulators will be able to leverage on the novel data set on market sentiment and asset prices to study patters of market reaction to changes in sentiment, such as procyclical asset purchases or asset reallocations.

Gerardo Martinez works in the Bank’s Capital Markets Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

[ad_2]